About Us

A History of the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia

by David Alonzo Stedman, Society Historian

That peculiar benevolence of mind which shews itself by charitable actions by giving relief to the poor and distressed has been always justly esteemed one of the first-rate moral virtues. Any persons then who form themselves into a society with this intention must certainly meet the approbation of every candid and generous mind, and we hope that it will plainly appear by the rules that follow, that the St. Andrew’s Society, of Philadelphia, was solely instituted with that view…

We who are natives of that part of Great Britain called Scotland and reside in the City of Philadelphia, meeting frequently with our country people here in distress who generally make application to some one or other of us for relief, have agreed to form ourselves into a society in order to provide for these indigents whereby they may be more easily, more regularly, and more bountifully supplied than could well be done in the common troublesome way of making occasional collections for such purpose. Thus it appears that the design of this society is fair, equitable, and innocent, and to convince the world that it is so, we thought it proper to take this method of making public our rules. – Advertisement of the Rules of the St. Andrew’s Society (1749)

The St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia, founded in November, 1747, for charitable, social, and benevolent reasons, is the oldest St. Andrew’s Society in continuous existence in America. It was founded by 25 prominent gentlemen of Philadelphia who were proud to call themselves British, “from that part of Great Britain called Scotland.” It is still, by its Charter, exclusively a gentleman’s club.

The Scots in Philadelphia

Charity, Fraternity and Social Security

By 1747, Philadelphia was the gateway to the West for many Scots—a fact suitably remembered by the National Monument to Scottish Immigration sponsored by the Society and dedicated in 2011—and the prominent Scottish gentlemen of Philadelphia were concerned to help them on their way. However, the original concept of the Society, named for Scotland’s patron saint, the Apostle Andrew, the First Called, was not simply to provide an almsgiving mechanism by which cases for relief of unfortunate Scots could be investigated and help extended. The St. Andrew’s Society from the first had some of the characteristics of a “fraternal benevolent group as well as the features of a kind of social security.” Members apparently contributed during their days of plenty in full realization that they themselves might be helped should they ever “fall upon lean years in the future.”

There also developed a form of “honorary membership” whereby Scots residing outside of Philadelphia contributed a sum to the Society and were therefore entitled to refer all appeals from unfortunate Scots who came under their purview to the Society for attention. Officers of the Royal Highlanders, Royal Americans, and Royal Navy are listed as early honorary members, as are many sea captains who gave residences in other colonies, the West Indies, and the British Isles. It was quite clear that the Society was not formed to support beggars, but rather to help Scotsmen who were suffering through troubled times, including escaped prisoners of war, indentured servants, refugees from Culloden and its aftermath, and victims of misfortune.

The original rule #2 of the Society read, in part, “In order to maintain a good understanding, acquaintance, and Fellowship with one another the members of the Society shall assemble at some convenient house in Philadelphia four times every year.” To this dictum the present St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia still subscribes, but also holds special meals in honor of St. Andrew on a day close to his saint’s day, November 30, and in honor of Robert Burns, Scotland’s great poet and “Scot of the Millennium.”

The Founders: Philadelphia’s Movers, and Shakers

From the surviving records were know the names of the twenty-five Scottish gentlemen, and about some of them that is all we know. They had in common Scottish birth, and “there was not a single ‘Mac’ to be found among their surnames.”

Officers: Dr. Thomas Graeme, Col. James Burd, James Trotter, John Inglis, Dr. Adam Thompson, WilliamMcIlvaine, Members: Alexander Annard, James Bell, John Bell, William Blair, David Dewar, Alexander Forbes, Lewis Gordon, David Hall, Alexander Hamilton, James Hutton, Capt. John Kidd, James Lindsay, David McIlvaine, John Nelson, Robert Philip, George Smith, Alexander Stedman, Charles Stedman and John Wallace

Some were Highlanders, but most were Lowlanders; a handful were veterans of the Stuart rising of the ’45 and had fought at Culloden. Doctors, lawyers, merchants, engineers, sea captains, soldiers and printers were included. The surgeon Dr. Thomas Graeme, elected first president, became Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania and was instrumental in the founding of Pennsylvania Hospital. Colonel James Burd of Ormiston, first vice-president, was an outstanding military engineer. James Trotter, the first clerk (secretary) was an importer of broad cloth, while first treasurer John Inglis was a successful merchant and later served as Captain of the First Company, Associated Regiment of Foot, and deputy collector of the Port of Philadelphia. The early minutes did not record a roll call, only the names of those absent without a sufficient excuse, who were therefore fined. The fines helped swell the purse to provide assistance. It became the custom that when a Lieutenant Governor of Pennsylvania was a Scotsman (and later when a Governor of Pennsylvania was a Scotsman) that that man would also serve as president of the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia. James Hamilton and Robert Hunter Morris were the Penns’ resident Lieutenant Governors of the Province who served likewise as presidents of the Society, and subsequently Pennsylvania Commonwealth Governors Edwin Sidney Stuart and William Cameron Sproul were named to head the Society during their terms. Four members of the Society—James Wilson, Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon, George Ross, and Philip Livingston—signed the Declaration of Independence. Signer Thomas McKean later joined the Society and served three terms as Governor of Pennsylvania. James Wilson was the “father” of the US Constitution, a signer of the Constitution, and was appointed by President Washington as one of the first justices on the U.S. Supreme Court. John Witherspoon, DD, was president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University).

Some were Highlanders, but most were Lowlanders; a handful were veterans of the Stuart rising of the ’45 and had fought at Culloden. Doctors, lawyers, merchants, engineers, sea captains, soldiers and printers were included. The surgeon Dr. Thomas Graeme, elected first president, became Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania and was instrumental in the founding of Pennsylvania Hospital. Colonel James Burd of Ormiston, first vice-president, was an outstanding military engineer. James Trotter, the first clerk (secretary) was an importer of broad cloth, while first treasurer John Inglis was a successful merchant and later served as Captain of the First Company, Associated Regiment of Foot, and deputy collector of the Port of Philadelphia. The early minutes did not record a roll call, only the names of those absent without a sufficient excuse, who were therefore fined. The fines helped swell the purse to provide assistance. It became the custom that when a Lieutenant Governor of Pennsylvania was a Scotsman (and later when a Governor of Pennsylvania was a Scotsman) that that man would also serve as president of the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia. James Hamilton and Robert Hunter Morris were the Penns’ resident Lieutenant Governors of the Province who served likewise as presidents of the Society, and subsequently Pennsylvania Commonwealth Governors Edwin Sidney Stuart and William Cameron Sproul were named to head the Society during their terms. Four members of the Society—James Wilson, Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon, George Ross, and Philip Livingston—signed the Declaration of Independence. Signer Thomas McKean later joined the Society and served three terms as Governor of Pennsylvania. James Wilson was the “father” of the US Constitution, a signer of the Constitution, and was appointed by President Washington as one of the first justices on the U.S. Supreme Court. John Witherspoon, DD, was president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University).

Among the many Scotsmen from the founding period about whose lives something is known is David Hall, an Edinburgh printer, who had emigrated to Pennsylvania and entered into partnership with one Benjamin Franklin, later purchasing Dr. Franklin’s share of the business; Hall and Sellers were printers to the Society, and Dr. Franklin was a frequent guest at the meetings of the Society. Following a sumptuous repast at the Annual Dinner in 1760, at which Dr. Franklin had imbibed a considerable amount, the Society asked him to reimburse for broken wine glasses and to replace three chairs. When called upon to pay, Dr. Franklin was unrepentant and suggested that he come to the next meeting to see how much more damage he could do. It is a matter of record that he was not invited the following year, by unanimous vote of the Society.

General Hugh Mercer (left), hero of the French-Indian War (who had fought for Charles Edward Stuart at Culloden), was a Society member and appointed surgeon general of the Continental Army under General Washington. General Mercer was mortally wounded at the Battle of Princeton, January 4, 1777. His sword is one of the Society’s prized possessions, and since 1840 his remains, translated to a monumental tomb at Laurel Hill Cemetery, have been honored and cared for by the Society.

Robert Smith, arguably Philadelphia’s most able colonial architect, is remembered for churches, college halls, private homes, the steeple of Christ Church, Philadelphia (1754),for many years America’s tallest structure, and the gem of Carpenter’s Hall, newly finished in time for the meeting of the 1st Continental Congress. Smith caught a chill and died while placing obstacles of his design in the Delaware River to halt the advance of the Royal Navy.

Several of the Society’s members remained Tories during the Revolution, including Captain John Pitcairn, who was mortally wounded while leading the British troops at the Battle of Bunker Hill. The founding brothers Charles and Alexander Stedman lost all their wealth, including a famous home in Philadelphia (now the Powel House) and 10,000 acres of Lancaster County, due to remaining loyal to the king. Members of Alexander’s family had fought at Culloden. The younger brother, Charles, whose life is described in Kenneth Roberts novel “Oliver Wiswell,” with the rank of colonel, served as head of the commissary of the British Army in North America under Sir William Howe. He and his brother had managed many ships bringing Palatine Germans to America and so spoke German, necessary to deal with the Hessian mercenaries. Charles was taken prisoner and exchanged, and later, in London, wrote a two-volume history of the Revolution, from the British Loyalist perspective, arguing that Lord Howe could and should have ended the war victoriously in 1776. Charles died in 1812. [It has been mirthfully noted that two Stedman brothers (and a son) are still members of the Society; one “Tory” serves as historian.]

Several of the Society’s members remained Tories during the Revolution, including Captain John Pitcairn, who was mortally wounded while leading the British troops at the Battle of Bunker Hill. The founding brothers Charles and Alexander Stedman lost all their wealth, including a famous home in Philadelphia (now the Powel House) and 10,000 acres of Lancaster County, due to remaining loyal to the king. Members of Alexander’s family had fought at Culloden. The younger brother, Charles, whose life is described in Kenneth Roberts novel “Oliver Wiswell,” with the rank of colonel, served as head of the commissary of the British Army in North America under Sir William Howe. He and his brother had managed many ships bringing Palatine Germans to America and so spoke German, necessary to deal with the Hessian mercenaries. Charles was taken prisoner and exchanged, and later, in London, wrote a two-volume history of the Revolution, from the British Loyalist perspective, arguing that Lord Howe could and should have ended the war victoriously in 1776. Charles died in 1812. [It has been mirthfully noted that two Stedman brothers (and a son) are still members of the Society; one “Tory” serves as historian.]

The Charitable Work of the Society

The charitable work of the Society was performed by members called “assistants”—not “almoners” who would traditionally toss a beggar a coin or two. The Society never intended to sustain those who would not work to better themselves. A glance at the minutes which describe assistance rendered over the years reveals two constants: one, that the distress must only be a temporary setback and the recipient must be grateful and eager to repay; and, two, that the self-respect of the recipient is to be maintained. The task of the Society, then, was to give Scottish immigrants “a helping hand” whether it was a cash grant, a chance to find a job, or just good advice. The men met quarterly for drinks and dinner, and considered requests of assistance. And as the gentlemen of St. Andrew’s met for their stated purpose, they also enjoyed sharing jokes and songs, and discussing Scotland and current affairs. Over the years, thousands of immigrants received help, and the money for this charity was raised from dues, guest fees, and the generous gifts and bequests from the members. The Minute Book accounted for the funds, so we know the expenses to the penny. In 1758, 100 pounds sterling was let out at interest. A formidable early legacy was from William McKenzie who, in 1829, left the large sum of $1000.

According to historian Peter Reichner Hill (whose pioneering pamphlet I have quoted without attribution) an editor of AN HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE ST. ANDREW’S SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA… (1997) p. 7 “Hundreds of Scots benefitted from the largesse of society’s members in the second half of the 18th century. This generosity continued during periods of steady migration in the 19th century and particularly during the Great Depression of the 1930’s when the chief purpose of the Society was to provide food, coal, clothing and work to scores of distressed Scottish families… Fortunately, most people of Scottish ancestry, with their frugal work ethic, diligently and successfully avoid financial distress. This has enabled our Society’s members to develop additional outlets in which to serve. “

Edgar S. Gardner, ed. In THE FIRST TWO HUNDRED YEARS 1747-1947 OF THE ST. ANDREW’S SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA (1947,2008) p. 43 puts it this way: “So it goes, a long list of small deeds which, added together for [more than] 200 years, has made a tradition that is a great source of pride and inspiration to the present members of the St. Andrew Society. Whether it is distress of debtors’ jail, travel of colonial days or of unemployment, illness, or economic depression of more modern times, the need is as pressing, the help is prompt, and the appreciation is sincere.”

The Quarterly Supper Fund, the Library, and the Society’s “Relics”

By the middle of the 19th century there was a successful effort to endow the Quarterly Suppers, led by the industrialist Charles Macalester, so that members could concentrate their actual giving to “assistance.” The fund still pays for the the Quarterly Suppers, which are served for the most part at the Philadelphia Racquet Club, which houses the offices and library of the Society, and where the “relics” and special artifacts acquired through the years are preserved. These artifacts include Gen. Mercer’s sword (acquired in 1841) which is still carried in procession at the St. Andrew’s Day annual dinner, two ram’s head “snuff mills” which are also carried in procession, a large silver loving cup, historic gavels, a treasurer’s box, the Society’s “Johnston Decanter” of Edinburgh crystal, and a silver Quaich that is used to “pay the piper” at the end of the Haggis Ceremony. The Library, founded in 1907 by Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, a noted physician, was for many years the only Scottish library in the USA. Among its treasures is the complete original Census of Scotland, the 21-volume set of Sir John Sinclair’s STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF SCOTLAND (1791-99), as well as the tartan book of the Sobieski brothers with its colored plates and surprising revelations.

By the middle of the 19th century there was a successful effort to endow the Quarterly Suppers, led by the industrialist Charles Macalester, so that members could concentrate their actual giving to “assistance.” The fund still pays for the the Quarterly Suppers, which are served for the most part at the Philadelphia Racquet Club, which houses the offices and library of the Society, and where the “relics” and special artifacts acquired through the years are preserved. These artifacts include Gen. Mercer’s sword (acquired in 1841) which is still carried in procession at the St. Andrew’s Day annual dinner, two ram’s head “snuff mills” which are also carried in procession, a large silver loving cup, historic gavels, a treasurer’s box, the Society’s “Johnston Decanter” of Edinburgh crystal, and a silver Quaich that is used to “pay the piper” at the end of the Haggis Ceremony. The Library, founded in 1907 by Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, a noted physician, was for many years the only Scottish library in the USA. Among its treasures is the complete original Census of Scotland, the 21-volume set of Sir John Sinclair’s STATISTICAL ACCOUNT OF SCOTLAND (1791-99), as well as the tartan book of the Sobieski brothers with its colored plates and surprising revelations.

It may be interesting to note the frugal and sober Scots wrote into their By-Laws that “[i]n order to observe that frugality which becomes a charitable society, the four assistants shall take care at the quarterly meetings to provide a neat and plain supper, and shall call for and settle the bill at eleven o’clock, at furthest every meeting, except St. Andrew’s night and at nine o’clock furthest on that night.” The By-Laws also stated: “Nor shall any liquor be brought into the company but what is ordered by the assistants, and if any member shall stay after the bill is settled, their expenses shall be paid wholly by themselves.”

Some members have facetiously suggested that charitable activities are so arduous for Scots that they require vast quantities of food and drink to endure the pain of parting with their hard-earned money. In the past some dinners have been mightily restorative, as at one “neat and plain supper” on September 3, 1755 where thirty members consumed “two hams, a round of beef, a sirloin of beef, four tongues, a dozen of fowls, a side of lamb, 10 pounds of veal, pigeon pie, pound of butter, 5 pounds of cheese, and 10 six penny loaves.” Nor was drink neglected, as on December 1, 1788, when the 45 gentlemen of St. Andrew’s consumed “38 bottles of madeira, 27 bottles of claret, 8 bottles of port wine, 2 bowls of punch, plus Welsh rabbit, bread and cheese.”

The Evolution of the Insignia

The original rules of 1749 state”[a] large Seal shall be provided for use of the Society, with a thistle and crown over it, together with the motto ‘Nemo Me Impune Lacessit.’” A seal was obtained in 1750, though following the Revolution the crown was deemed inappropriate and removed. Then, in 1896, the Society adopted “Arms” consisting of a triangularly shaped shield bearing the figure of St. Andrew and his cross, mounted within a circular belt bearing the motto, and included a thistle at the buckle of the belt. In 1904 “Insignia” was adapted, consisting of a metal badge suspended from a ribbon, and in 1907 the “Badge” was adopted as the official “Arms” of the Society. This Insignia is used as the basis for the medallions worn by presidents and past-presidents of the Society. Certificates are given to new members of the Society, using an embossed seal bearing the original insignia of the Thistle (without the crown), the original motto which translates “No one injures me with impunity,” and the date 1747. It is believed this certificate was originally engraved in 1792 by Robert Scot, first engraver of the US Mint. Society members wear a rosette, comprising the colors of the Society, conceived by E. Harding McIntyre and worn proudly since 1947. The present arms of the Society include the arms of the USA and Scotland and St. Andrew with his cross, the oval once again crowned and encircled by a wreath of thistles with the motto on a belt.

The Scholarships, the Foundation, and the 1747 Society (which helps fund them)

Following World War II, with Scottish emigration down to a trickle and social safety nets enacted by Congress, the Society turned its interest to helping young people. The mission, as reconceived, was to develop leadership through study for a year at Scottish universities, thereby “promoting good relations between our two nations.” The first St. Andrew’s Society scholar traveled to St. Andrew’s University in Scotland in 1957. There have been more than 260 since then, with (often) six Americans studying in Scotland’s historic universities and one Scot studying at the University of Pennsylvania. [see Scholarship Program]. A non-profit corporation that was established in 1958 as the “Foundation of the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia” has as its goal to “promote understanding between the United States and Scotland by awarding scholarships to carefully selected men under 35 years of age to attend institutions of higher learning in Scotland.” [This award is now made to young women scholars at colleges in the Philadelphia area as well.] Members of the Society who contribute to the Foundation become members, and those who indicate that they have made provision for the Foundation in their wills and estates may earn the distinction of being a part of “The 1747 Society.”

The Monument(s)

On October 8, 2011 an impressive monument to honor Scottish Immigration to America sculpted by Society member Terry Jones was unveiled on Penn’s Landing, Philadelphia, by its patron, His Grace Torquhil Ian Campbell, 13th Duke of Argyll and The 28th MacCailein Mor, chief of Clan Campbell. This monument came into fruition by the generosity of many members of the Society, by contributions from other St. Andrew’s Societies and their members, from clan societies and foundations, and from several firms in Scotland. His Grace said that the National Monument to Scottish Immigration stood for immigration from the mother country of Scots who brought their skills, talents, and energy not just to America but to many countries around the world.

Though it represents a Highlander family arriving in Philadelphia in the mid-18th century full of hope for a new life in the New World, it also commemorates all of the Scots and Scots-Irish who have come to America in the past, now, and in the future. The duke took the idea further, saying it suitably represents brave, hardy, inventive Scots who carried Western culture to lands all around the globe and helped make their homeland one of the most important and revered nations in modern history. At a reception and banquet for 140 in the Union League of Philadelphia following the unveiling of the monument, the duke responded with sincere pleasure to a toast directed to him as a patron who had actively raised more than $100,000 for the National Monument from the whisky distilleries in Scotland.

Our Society’s First National Scottish American Monument

“The Call”: A Symbol of Patriotism for all Peoples.

As we reflect on the monument to Scottish immigration unveiled on October 8, 2011, and all the labor of love that has promoted it in our time, we should recall that this is the second monument sponsored and brought to fruition by The St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia. An earlier one was unveiled on September 7, 1927.

As we reflect on the monument to Scottish immigration unveiled on October 8, 2011, and all the labor of love that has promoted it in our time, we should recall that this is the second monument sponsored and brought to fruition by The St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia. An earlier one was unveiled on September 7, 1927.

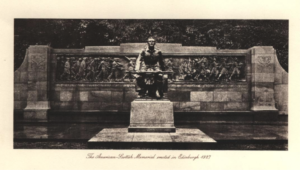

“The Call” a bronze statue by Dr. R. Tait McKenzie, president of the Society 1923-24, sits in Princes Street Gardens, in Edinburgh, the centerpiece of the Scottish American War Memorial commemorating Scottish valor in the Great War of 1914-18. The heroic seated soldier figure, in uniform and kilt with his rifle across his knees, answers, in the hour of Scotland’s danger, “the Call” of Scottish blood. On the wall behind him, on a bronze frieze of the Marching Scots, are all manner of men from all walks of life, marching with determination, with courage, and with comradeship; the epitome of “Scotland the Brave”—and of brave men everywhere.

On the stone underneath the frieze runs an inscription cut in sixteenth century Scottish lettering:

If it be life that waits,

I shall live forever unconquered,

If death, I shall die at last

Strong in my pride and free.

The St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia spearheaded this tribute from men and women of Scottish blood and sympathies in the United States of America to Scotland, and although representatives from nearly every state in the Union served on the National Committee and support came from all quarters, the administrative and financial responsibilities were underwritten by the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia. The idea for such a monument to the valor of Scottish soldiers in the battles of World War I originated with John Gordon Grey, president of the Society 1912-13, and the well-known sculptor of young and vigorous heroes, Tait McKenzie, beautifully translated into the young hero answering the Call, the mystery of youthful and patriotic service that transcends any one people.